An exhaustive Python cheat sheet 2/2

After a 1st post covering the core concepts, this 2nd part focus on the Object Oriented part of Python and on functionnal programming. You can find all of this content in a dedicated anki deck WIP to help you memorizing it.

Cards are composed of a simple challenge, then answer shows the code and its’ result in a dedicated jupyter notebook also available on github.

This is a summary of the most important key features and syntax of the language. It was made in order to create an anki deck for memorizing the below examples

Functions

A function is a block of code which only runs when it is called. You can pass data, known as parameters, into a function. A function can return data as a result.

A function prototype

def function_name(parameters ):

"""function_docstring

on multiple lines"""

#function_suite

return [expression]

a simple example of a print_me function

def print_me(str):

"""print the input str"""

print(str)

print_me("Hello")

Hello

How parameters (arguments) in Python are passed ?

by reference: if you change what a parameter refers to within a function, the change also reflects back in the calling function.

def append_lst(lst, param):

# reference passed

lst.append(param)

my_lst = [1, 'a', 2.3]

append_lst(my_lst, 'b')

my_lst

[1, 'a', 2.3, 'b']

def change_lst(lst):

# assign a new reference

lst = ['a', 'b', 'c']

my_lst = [1, 2, 3]

change_lst(my_lst)

my_lst

[1, 2, 3]

Explanation of what is namespace separation

A namespace is a region of a program in which identifiers have meaning. When a Python function is called, a new namespace is created for that function, one that is distinct from all other namespaces that already exist.

In practice, this is that variables can be defined and used within a Python function even if they have the same name as variables defined in other functions or in the main program. In these cases, there will be no confusion or interference because they’re kept in separate namespaces.

This means that when you write code within a function, you can use variable names and identifiers without worrying about whether they’re already used elsewhere outside the function. This helps minimize errors in code considerably.

example of positional arguments

The most straightforward way to pass arguments is with positional arguments (also called required arguments). Order is important:

def you(name, age):

print(f'{name} is {age} yrs old')

you("Loic", 20)

Loic is 20 yrs old

you("Loic")

# TypeError: you() missing 1 required

# positional argument: 'age'

you("Loic", 20, ['t', '1'])

# TypeError: you() takes 2 positional

# arguments but 3 were given

example with global vs. local variables

y = 10

def sum(x):

return x+y

sum(1)

11

y

10

x

# NameError: name 'x'

# is not defined

Example of keyword arguments

you specify arguments in the form <keyword>=<value>. Each <keyword> must match a parameter in the function definition. The number of arguments and parameters must still match.

def you(name="Loic", age=20):

print(f'{name} is {age} yrs old')

you("Abdel", 30)

Abdel is 30 yrs old

lifts the restriction on argument order

you(age=10, name="Louis")

Louis is 10 yrs old

you(name="Louis", cost=10)

# TypeError: you() got an unexpected

# keyword argument 'cost'

call a function using both positional and keyword arguments:

def you(name="Loic", age=20):

print(f'{name} is {age} yrs old')

you(30, "Abdel")

30 is Abdel yrs old

you("Ali", age=5)

Ali is 5 yrs old

you(name="Marc", 0)

# SyntaxError: positional argument

# follows keyword argument

Example of default parameters

If a parameter specified in a function definition has the form <name>=<value>, then <value> becomes a default value for that parameter. They are referred to as default or optional parameters. Any argument that’s left out assumes its default value:

def you(name, age=20):

print(f'{name} is {age} yrs old')

you("Max")

Max is 20 yrs old

def you(name="Mo", age):

print(f'{name} is {age} yrs old')

you(20)

# SyntaxError: non-default argument

# follows default argument

summary of arguments / parameters:

- Positional arguments must agree in order and number with the parameters declared in the function definition.

- __Keyword argument__s must agree with declared parameters in number, but they may be specified in arbitrary order.

- Default parameters allow some arguments to be omitted when the function is called.

Mutable default parameter values

default parameter values are defined only once when the function is defined

def f(my_list=[]):

print(id(my_list))

my_list.append('##')

return my_list

f([1, 2])

1789862290432

[1, 2, '##']

f([1, 2, 3])

1789862258560

[1, 2, 3, '##']

f()

1789862291584

['##']

f()

1789862291584

['##', '##']

# workaround

def f(my_list=None):

if my_list is None:

my_list = []

my_list.append('##')

return my_list

Argument passing summary

-

Passing an immutable object (an int, str, tuple, or frozenset) acts like pass-by-value: the function can’t modify the object in the calling environment.

-

Passing a mutable object (a list, dict, or set) acts somewhat—but not exactly—like pass-by-reference: the function can’t reassign the object wholesale, but it can change items in place within the object & these changes will be reflected in the calling environment.

the return statement purposes

1.It immediately terminates the function and passes execution control back to the caller.

2.It provides a mechanism by which the function can pass data back to the caller.

def f():

print('foo')

return

print('bar')

f()

foo

This sort of paradigm can be useful for error checking in a function:

def f():

if error_cond1:

return

if error_cond2:

return

<normal processing>

Example of returning data to the caller

a function can return any type of object. In the calling environment, the function call can be used syntactically in any way that makes sense for the type of object the function returns.

def f():

return dict(foo=1, bar=2)

f()

{'foo': 1, 'bar': 2}

f()['bar']

2

def f():

return 'foobar'

f()[2:4]

'ob'

f()[::-1]

'raboof'

An example of a function that returns multiple elements

def f():

return 'a', 1, 'b', 2

f()[2]

'b'

type(f())

tuple

x, *_, z = f()

x, z

('a', 2)

An example of a function that returns nothing

def f():

return

print(f())

None

def g():

pass

print(g())

None

An example of a function that doubles an int

def f(x):

x *= 2

x = 5

f(x)

x

5

this won’t work because integers are immutable,

so a function can’t change an integer argument

def g(x):

return x * 2

x = 5

x = g(x)

x

10

An example of a function that doubles values of a list (by side effect or not)

def double_list(x):

i = 0

while i < len(x):

x[i] *= 2

i += 1

a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

double_list(a)

a

[2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

def double_list(x):

return [e*2 for e in x ]

a = [1, 2, 3, 4, 5]

a = double_list(a)

a

[2, 4, 6, 8, 10]

Argument Tuple Packing

when the nb of arguments is not defined and a tuple is probably not something the user of the function would expect. To pass a function a variable nb of arguments use the asterisk (*) operator.

def my_avg(*args):

return sum(args) / len(args)

my_avg(1, 2, 3)

2.0

my_avg(1, 2, 3, 4)

2.5

Argument Dictionary Packing

the double asterisk (**) can be used to specify dictionary packing and unpacking : the corresponding arguments is expected to be key=value pairs and should be packed into a dictionary (and not considered as a dict):

def dict_arg(**kwargs):

print(kwargs)

dict_arg(foo=1, bar=2, baz=3)

{'foo': 1, 'bar': 2, 'baz': 3}

dict_arg({"foo":1, "bar":2, "baz":3})

# TypeError: dict_arg() takes 0

# positional arguments but 1 was given

Credits: Real Python dot com

An example of a function with standard positional parameters, args, and kwargs

def f(a, b, *args, **kwargs):

print(a, b)

print([x*2 for x in args])

print({k:v+1 for k, v in kwargs.items()})

f(1,2, 'foo', 'bar', x=100, y=200, z=300)

1 2

['foofoo', 'barbar']

{'x': 101, 'y': 201, 'z': 301}

Multiple Unpackings args in a Python Function Call

def f(*args):

for i in args:

print(i)

a, b = [1, 2, 3], ['a', 'b', 'c']

f(*a, *b)

1

2

3

a

b

c

Multiple Unpackings kwargs in a Python Function Call

def f(**kwargs):

for (k, v) in kwargs.items():

print(k, "-->", v)

a, b = {'a': 1, 'b': 2}, {'x': 100, 'y': 200}

f(**a, **b)

a --> 1

b --> 2

x --> 100

y --> 200

Keyword-Only Arguments

Keyword-only arguments allow a Python function to take a variable number of arguments, followed by one or more additional options as keyword arguments.

def concat(*args, prefix='-> ', sep='.'):

print(f'{prefix}{sep.join(args)}')

concat('a', 'b', 'c')

-> a.b.c

concat('a', 'b', 'c', prefix='//')

//a.b.c

concat('a', 'b', 'c', prefix='//', sep='-')

//a-b-c

Docstrings

def foo(bar=0, baz=1):

"""Perform a foo transfo.

Keyword arguments:

bar -- blabla (default=1)

baz -- blabla (default=1)

"""

#<function_body>

print(foo.__doc__)

Perform a foo transfo.

Keyword arguments:

bar -- blabla (default=1)

baz -- blabla (default=1)

In the interactive Python interpreter,

help(foo)

Help on function foo in module __main__:

foo(bar=0, baz=1)

Perform a foo transfo.

Keyword arguments:

bar -- blabla (default=1)

baz -- blabla (default=1)

Python Function Annotations

- Annotations provide a way to attach metadata to a function’s parameters & return value.

- They don’t impose any semantic restrictions on the code

- They make good documentation (add clarity to docstring)

def f(a: int = 12, b: str = 'baz') -> float:

print(a, b)

return(3.5)

f.__annotations__

{'a': int, 'b': str, 'return': float}

f()

12 baz

3.5

f('foo', 2.5)

foo 2.5

3.5

Enforcing Type-Checking

cf. PEP 484 and use mypy, a free static type checker for Python

when passing a mutable value as a default argument in a function, the default argument is mutated anytime that value is mutated

def append_lst(lst=[]):

lst.append("aaa")

return ["zzz"] + lst

append_lst()

['zzz', 'aaa']

append_lst()

['zzz', 'aaa', 'aaa']

def f(value, key, hash={}):

hash[value] = key

return hash

print(f('a', 1))

print(f('b', 2))

{'a': 1}

{'a': 1, 'b': 2}

and not as expected

{‘a’: 1}

{‘b’: 2}

solution to mutable value as a default argument in a function

Use None as a default and assign the mutable value inside the function.

def append(element, seq=None):

if seq is None:

seq = []

seq.append(element)

return seq

append(1) # `seq` is assigned to []

[1]

append(2) # `seq` is assigned to [] again!

[2]

Lambda

Sorting with lambda

scientists = [ 'M. Curie', 'A. Einstein',

'N. Bohr', 'C. Darwin']

sorted(scientists, key=lambda name: name.split()[-1])

#sorted(iterable, key(callable))

['N. Bohr', 'M. Curie', 'C. Darwin', 'A. Einstein']

An example of a lambda with a tuple as input

(lambda x, y: x + y)(2, 3)

5

Detecting Callable Objects

def is_even(x):

return x % 2 == 0

callable(is_even)

True

is_odd = lambda x: x % 2 == 1

callable(is_odd)

True

callable(list)

True

callable(list.append)

True

class CallMe:

def __call__(self):

print("Called!")

callable(CallMe())

True

Object Oriented Programming

This part is based on the examples provided in the excellent course by Joe Marini @LinkedinLearning

Why OOP ?

- not required to code in Python

- but complex programs are hard to keep organized

- OOP can structure code

- group together data & behavior into one place

- promotes modularization of programs

- isolates parts of the code

Concepts / key terms

- Class = a blueprint for creating objects of a particular type

- Methods = regular functions that are part of a class

- Attributes = variables that hold data that are part of a class

- Object = a specific instance of a class

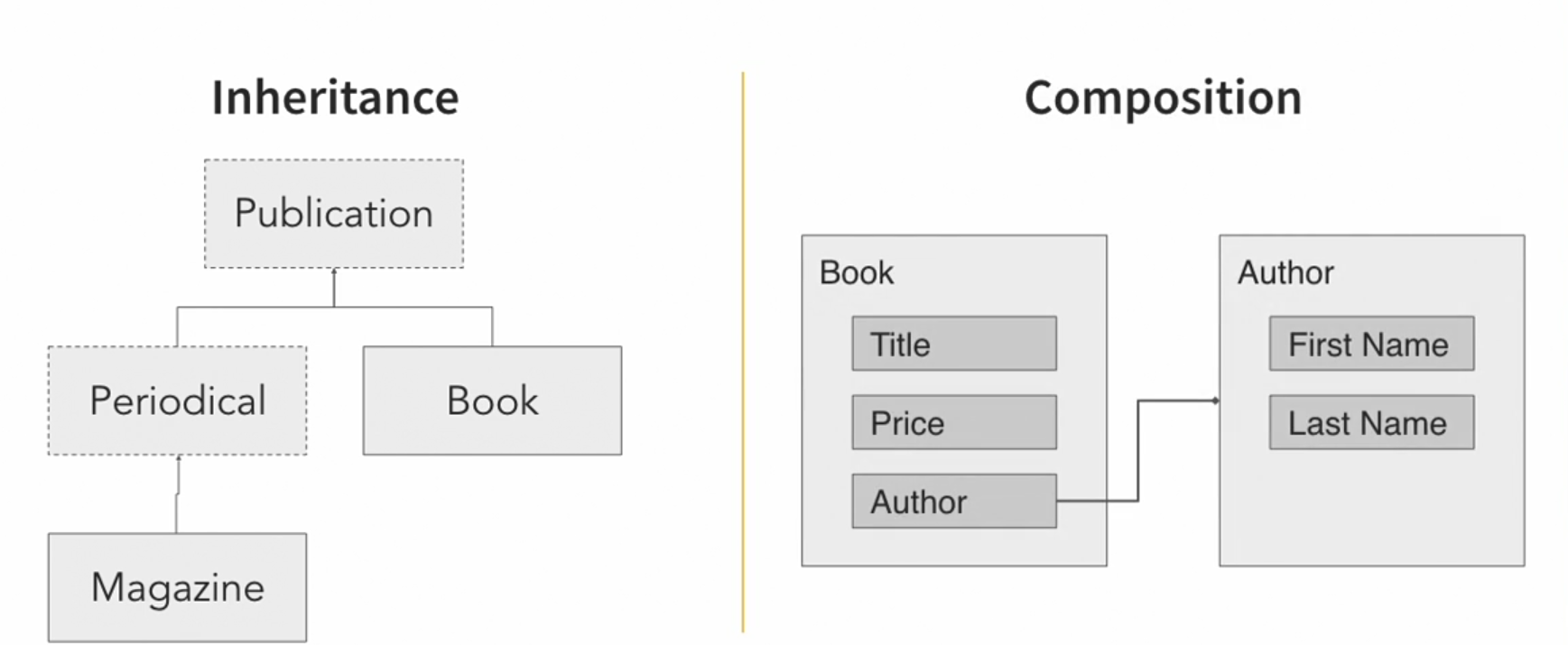

- Inheritance = means by which class can inherit capabilitites from another

- Composition = means of buiding complex objects out of other objects

Basic class definition

create a basic class, an instance & print the class proerty

class Book():

# the "init" function is called when

# the instance is created & ready to

# be initialized

def __init__(self, title):

self.title = title

b1 = Book("Brave New World")

b1.title

'Brave New World'

Instance methods and attributes

class Book():

def __init__(self, title, author, pages, price):

self.title = title

self.author = author

self.pages = pages

self.price = price

def get_price(self):

if hasattr(self, "_discount"):

return self.price * (1 - self._discount)

else:

return self.price

def set_discount(self, amount):

self._discount = amount

b1 = Book("Brave New World", "L. Tolstoy", 1225, 39.95)

b2 = Book("War and Piece", "JD Salinger", 234, 29.95)

print(b1.get_price())

print(b2.get_price())

b2.set_discount(0.25)

print(b2.get_price())

39.95

29.95

22.4625

What _ & __ are used for ?

- The _ indicates that an attribute or a method is intended to only be used by the class.

- With __ the interpreter will change the name of that attribute or method so that other classes will get an error.

- This prevent subclasses from inadvertently overriding the attribute but other classes can subvert this simply by using the class name.

- You can use this to make sure that subclasses don’t use the same name for an attribute or don’t have the right to overwrite it.

class Book():

def __init__(self, title):

self.title = title

self.__secret = "SecreT"

b1 = Book("Brave New World")

b1._Book__secret

'SecreT'

b1.__secret

# AttributeError: 'Book' object

# has no attribute '__secret'

Checking instance types

class Book():

def __init__(self, title):

self.title = title

class Newspaper():

def __init__(self, name):

self.name = name

b1 = Book("The Grapes of Wrath")

b2 = Book("The Catcher In the Rye")

n1 = Newspaper("The NY Times")

type(b1)

__main__.Book

type(n1)

__main__.Newspaper

type(b1) == type(b2)

True

type(b1) == type(n1)

False

isinstance(b1, Book)

True

isinstance(n1, Book)

False

isinstance(n1, object)

True

Class methods and members

attribute at the Class level

class Book():

# class attribute shared by all instances

BOOK_TYPES = ("Hardcover", "Paperback", "Ebook")

# a class method

@classmethod

def get_book_types(cls):

return cls.BOOK_TYPES

def set_title(self, new_title):

self.title = new_title

def __init__(self, title, booktype):

self.title = title

if (not booktype in Book.BOOK_TYPES):

raise ValueError(f"{booktype} is not valid")

else:

self.booktype = booktype

print("Book types: ", Book.get_book_types())

Book types: ('Hardcover', 'Paperback', 'Ebook')

b1 = Book("Title 1", "Hardcover")

# "Comics" instead of "Hardcover" will raise an error

Static method example

Static methods don’t modify the state of either the class or a specific object instance. Not so many use case : when you don’t need to access any properties of a particular object or the class itself, but it makes sense for the method to belong to the class.

The are global functions in the class namespace.

Example : singleton

Inheritance & Composition

Understanding inheritance

An example to show how to create multiples classes inherited to an other

class Publication():

def __init__(self, title, price):

self.title = title

self.price = price

class Periodical(Publication):

def __init__(self, title, price, period, publisher):

super().__init__(title, price)

self.period = period

self.publisher = publisher

class Book(Publication):

def __init__(self, title, author, pages, price):

super().__init__(title, price)

self.author = author

self.pages = pages

class Magazine(Periodical):

def __init__(self, title, publisher, price, period):

super().__init__(title, price, period, publisher)

class Newspaper(Periodical):

def __init__(self, title, publisher, price, period):

super().__init__(title, price, period, publisher)

b1 = Book('bbb', "me", 211, 19.5)

n1 = Newspaper('NY Times', 'my company', 6.0, 'Daily')

m1 = Magazine('Time', 'all', 5.5, 'Monthly')

print(b1.author)

print(n1.publisher)

print(m1.price, n1.price)

me

my company

5.5 6.0

Abstract base classes

You don’t want consumers of your base class to be able to create instances of the base class itself. Because it’s just intended to be a blueprint. Subclasses provide concrete implementations.

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class GraphicShape:

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

@abstractmethod

def calcArea(self):

pass

class Circle(GraphicShape):

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

def calcArea(self):

return 3.14 * (self.radius ** 2)

class Square(GraphicShape):

def __init__(self, side):

self.side = side

def calcArea(self):

return self.side ** 2

# g = GraphicShape()

# cannot be instantiate

c = Circle(10)

print(c.calcArea())

s = Square(12)

print(s.calcArea())

314.0

144

Using multiple inheritance

working example of a class C inherited from both A & B

class A:

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.foo = "foo"

class B:

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.bar = "bar"

class C(A, B):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

def showprops(self):

print(self.foo, self.bar)

c = C()

c.showprops()

foo bar

an other working example of a class C inherited from both A & B, but when both superclasses have the same property with different values.

Python looks in the superclasses in the order in which they are defined from left to right

class A:

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.foo = "foo"

self.name = "Class A"

class B:

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

self.bar = "bar"

self.name = "Class B"

class C(A, B):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

def showprops(self):

print(self.foo, self.name)

c = C()

c.showprops()

print(C.__mro__)

foo Class A

(<class '__main__.C'>, <class '__main__.A'>, <class '__main__.B'>, <class 'object'>)

Interfaces

What is an interface ?

an interface is a kind of promise for a program behavior / capacity. It’s a programming feature. Unlike Java or C#, Python does not have explicit language support for this. But it is easy to implement

When to use an interface ?

When we want to create a very smal, focused class, that we can use whenever we want another class to be able to indicate. It gives the flexibility to apply this new class which is serving the function of an interface anywhere it is needed. Interfaces are really usefull for declaring that a class has a capability that it knows how to provide

An example of an interface

from abc import ABC, abstractmethod

class GraphicShape(ABC):

def __init__(self):

super().__init__()

@abstractmethod

def calcArea(self):

pass

class JSONify(ABC):

@abstractmethod

def toJSON(self):

pass

class Circle(GraphicShape, JSONify):

def __init__(self, radius):

self.radius = radius

def calcArea(self):

return 3.14 * (self.radius ** 2)

def toJSON(self):

return f"square: {str(self.calcArea())"

c = Circle(10)

print(c.calcArea())

print(c.toJSON())

314.0

{ "square": 314.0 }

Understanding composition

a concept that allows to create complex objects out of simpler ones. It is different than inheritance but both two are not exclusive. For instance, a monolithic class definition can be made more extensible & flexible by composiing it with simpler class objects, each of which is responsible for its own features & data.

class Book:

def __init__(self, title, price, author=None):

self.title, self.price = title, price

self.author = author

self.chapters = []

def add_chapter(self, chapter):

self.chapters.append(chapter)

def get_page_count(self):

result = 0

for ch in self.chapters:

result += ch.page_count

return result

class Author:

def __init__(self, f_name, l_name):

self.f_name, self.l_name = f_name, l_name

def __str__(self):

return f'{self.f_name} {self.l_name}'

class Chapter:

def __init__(self, name, page_count):

self.name, self.page_count = name, page_count

auth = Author("Leo", "Toltstoy")

b1 = Book("War & Piece", 39., auth)

b1.add_chapter(Chapter("Ch. 1", 123))

b1.add_chapter(Chapter("Ch. 2", 96))

print(b1.author, b1.title, b1.get_page_count())

Leo Toltstoy War & Piece 219

Magic Object Methods

A set of methods that Python automatically associates with every class definition. Your class can override these methods to customize a variety of behavior and make them act just like Python’s built-in classes.

- customize object behavior & integrate with the language

- define how objects are represented as strings (for user or debugging purpose)

- control access to attribute values, both for get and set

- built in comparison and equality testing capabilities

- allow objects to be called like functions (make code more concise & readable)

String representation

The str function is used to provide a user-friendly string description of the object, and is usually intended to be displayed to the user.

The repr function is used to generate a more developer-facing string that ideally can be used to recreate the object in tis current state (used for debugging purpose)

class Book:

def __init__(self, title, author, price):

super().__init__()

self.title, self.author = title, author

def __str__(self):

return f'{self.title} by {self.author}'

def __repr__(self):

return f'title={self.title}, auth={self.author}'

b1 = Book("The Catcher in the Rye", "JD Salinger", 29.95)

print(str(b1))

print(repr(b1))

The Catcher in the Rye by JD Salinger

title=The Catcher in the Rye, auth=JD Salinger

Equality and comparison

Why : plain objects in Python, by default, don’t know how to compare themselves to each other. It can be achieved with the equality & comparison magic methods. Python doesn’t compare objects attributes by attributes : it just compares 2 different instances to each other (same object in memory ?)

class Book:

def __init__(self, title, author, price):

super().__init__()

self.title = title

self.author = author

self.price = price

def __eq__(self, value):

if not isinstance(value, Book):

raise ValueError("Not a book")

return (self.title == value.title and

self.author == value.author)

b1 = Book("My Book", "Me", 20)

b2 = Book("My Book", "Me", 20)

b3 = Book("Your Book", "You", 30)

print(b1 == b2)

print(b1 == b3)

True

False

examples of greater and lesser magic methods

class Book:

def __init__(self, title, price):

super().__init__()

self.title = title

self.price = price

def __ge__(self, value):

if not isinstance(value, Book):

raise ValueError("Not a book")

return self.price >= value.price

def __lt__(self, value):

if not isinstance(value, Book):

raise ValueError("Not a book")

return self.price < value.price

b1 = Book("My Book", 40)

b2 = Book("Your Book", 30)

b3 = Book("Other Book", 20)

print(b1 >= b2)

books = [b1, b2, b3]

books.sort()

print([b.title for b in books])

True

['Other Book', 'Your Book', 'My Book']

Attribute access

Your class can define methods that intercept the process any time an attribute is set or retrieved. It gives you a great amount of flexibility and control over hwo attributes are retrieved and set in your classes.

__getattribute__ is similar to __getattr__, with the important difference that __getattribute__ will intercept EVERY attribute lookup, doesn’t matter if the attribute exists or not.

class Book:

def __init__(self, author, price):

super().__init__()

self.author = author

self.price = price

self._discount = 0.1

# Don't directly access the attr name

# otherwise a recursive loop is created

def __getattribute__(self, name):

if name == "price":

p = super().__getattribute__("price")

d = super().__getattribute__("_discount")

return p - (p * d)

return super().__getattribute__(name)

# Don't set the attr directly here otherwise

# a recursive loop causes a crash

def __setattr__(self, name, value):

if name == "price" and type(value) is not float:

raise ValueError("Not a float")

return super().__setattr__(name, value)

# pretty much generate attr on the fly

def __getattr__(self, name):

return name.upper()

b1 = Book("My book", 30.0)

print(b1.price)

b1.price = float(40)

print(b1.price)

print(b1.new_attr)

27.0

36.0

NEW_ATTR

Callable objects

Callable like any other function. This features is interesting when you have objects whose attributes change frequently or are often modified together (more compact code & easier to read)

class Book:

def __init__(self, title, price):

super().__init__()

self.title = title

self.price = price

def __str__(self):

return f'{self.title} ${self.price}'

def __call__(self, title, price):

self.title = title

self.price = price

b1 = Book('War & Piece', 39.95)

print(b1)

b1('My Book', 100.)

print(b1)

War & Piece $39.95

My Book $100.0

Data Classes

In 3.7 Python introduced a new feature called Data Class which helps to automate the creation and managing of classes that mostly exist just to hold data.

Defining a data class

Dataclasses have more benefits than concise code : they also automatically implement init, repr and eq magic methods

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Book:

title : str

author : str

pages : int

price : float

def book_infos(self):

return f'{self.title} ${self.price}'

b1 = Book("My Book", "Meh", 120, 2.5)

b2 = Book("My Book", "Meh", 120, 2.5)

print(b1)

Book(title='My Book', author='Meh', pages=120, price=2.5)

b1 == b2

True

b1.author

'Meh'

b1.book_infos()

'My Book $2.5'

b1.author = "YOU!"

print(b1)

Book(title='My Book', author='YOU!', pages=120, price=2.5)

Using post initialization

for example, we might want to create attributes that depends on the values of other attributes, but we can’t write init (the dataclass do it for us). The post_init is where you can add additionnal attr that might depend on other ones in your object.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Book:

title : str

price : float

def __post_init__(self):

self.infos = f'{self.title} ${self.price}'

b1 = Book("War & Piece", 13.5)

print(b1.infos)

War & Piece $13.5

Using default values

Dataclasses provide the ability to define values for their attributes subject to some rules.

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Book:

title : str = "No title"

author : str = "No author"

pages : int = 0

price : float = 0.0

b1 = Book()

b1

Book(title='No title', author='No author', pages=0, price=0.0)

Be aware that attributes without default values have to come first

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass

class Book:

price : float

title : str = "No title"

author : str = "No author"

pages : int = 0

b1 = Book(123.5)

b1

Book(price=123.5, title='No title', author='No author', pages=0)

if price is not declared first : TypeError: non-default argument ‘price’ follows default argument

An other solution is to use “field” :

from dataclasses import dataclass, field

@dataclass

class Book:

title : str = "No title"

author : str = "No author"

pages : int = 0

price : float = field(default=10.0)

b1 = Book(123.5)

b1

Book(title=123.5, author='No author', pages=0, price=10.0)

instead of the default values, you can also use a function outside the object definition

Immutable data classes

Occasionally you’ll want to create classes whose data can’t be changed : the data in them should be immutable. This is possible by specifiing an argument to the data class decorator.

The “frozen” parameter makes the class immutable

from dataclasses import dataclass

@dataclass(frozen=True)

class ImmutableClass:

value1: str = "Value 1"

value2: int = 0

def some_meth(self, new_val):

self.value2 = new_val

obj = ImmutableClass()

print(obj.value1)

Value 1

obj.some_meth(100)

# FrozenInstanceError:

# cannot assign to field 'value2'