ELF binary compilation of a python script - part 1 : Cython

Banner comes from a cropped photo by Yancy Min on Unsplash

Introduction

In the past, i’ve made several system programs in C in order to complete various task at a relatively low level of the OS.

Since two years, i code in Python on a daily basis mostly for Data Science / Engineering projects, but from time to time for scrapping, web apps or in order to automate the boring stuff.

Python can also be used for administrative tasks. Even though it is not intended for very low level stuff like the ones C or ASM can do, it is easier to maintain than shell scripting, and above all it comes with a lots of libraries.

Anyway, distribution of python packages or apps is often a tedious tasks on production environnement because, as a system admin it is against the policy to add external libraries (which wouldn’t be maintained anymore in a near future or comes with potential vunerabilities…). Furthermore, OS and configurations can vary among all the big data cluster’s nodes i’ve been in charge to administrate…

This is where creating an elf binary with all the dependencies (i.e needed libraries) can be interesting ! In this series of posts i’ll try various utilities that aims to solve the problem of how to distribute Python applications.

An interesting comparison to other tools can be found on the PyOxidizer documentation.

In this first part i’ll use cython. Later i’ll probably explore Nuitka, PyInstaller and PyOxidizer.

Cython: C-Extensions for Python

Cython is a really powerfull tool. As stated in the official documentation : It is an optimising static compiler for both the Python programming language and the extended Cython programming language (based on Pyrex). It makes writing C extensions for Python as easy as Python itself.

Cython gives you the combined power of Python and C to let you

- write Python code that calls back and forth from and to C or C++ code natively at any point.

- easily tune readable Python code into plain C performance by adding static type declarations, also in Python syntax.

- use combined source code level debugging to find bugs in your Python, Cython and C code.

- interact efficiently with large data sets, e.g. using multi-dimensional NumPy arrays.

- quickly build your applications within the large, mature and widely used CPython ecosystem.

- integrate natively with existing code and data from legacy, low-level or high-performance libraries and applications.

I’ve used numpy for a long time now, and cython looks so attractive in order to optimize python code, but here, i’ll mainly use cython in order to compile code. Let’s start with this snippet :

import os

os_info = os.uname()

#print(os_info)

print("name : ", os_info[0])

print("name of machine on network : ", os_info[1])

print("release : ", os_info[2])

print("version : ", os_info[3])

print("machine : ", os_info[4])

name : Linux

name of machine on network : my_user_name-desktop

release : 5.3.0-51-generic

version : #44~18.04.2-Ubuntu SMP Thu Apr 23 14:27:18 UTC 2020

machine : x86_64

When executing the python interpreter, it provides the following result on my box :

!python3 test.py

name : Linux

name of machine on network : my_user_name-desktop

release : 5.3.0-51-generic

version : #44~18.04.2-Ubuntu SMP Thu Apr 23 14:27:18 UTC 2020

machine : x86_64

Let’s see which version of cython am i using :

!cython --version

Cython version 0.29.13

Typically Cython is used to create extension modules for use from Python programs. It is, however, possible to write a standalone programs in Cython. This is done via embedding the Python interpreter with the –embed option. (Reference)

!cython -3 test.py --embed

!ls -ahl

-rw-r--r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 127K mai 9 17:31 test.c

-rw-rw-r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 224 déc. 14 13:42 test.py

Static vs Dynamic Linking

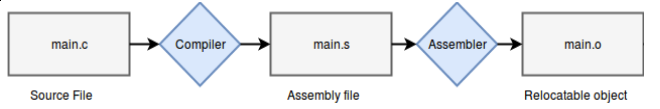

First, linking is the process of joining together multiple object files, to create a shared library or an executable. This post serie by Intezer is a great ressource.

There are two linking types:

- Static linking: Completed at the end of the compilation process

- Dynamic linking: Completed at load time by the system

Static linking is fairly simple:

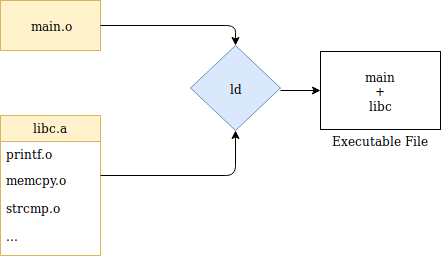

The compile-time linker (ld) collects all relevant object files—main.o and the libc.a static library (a bundle of object-files)—applies relocations and combines the files into a single binary. As such, when many object files are linked, the resulting binary file size can become very large.

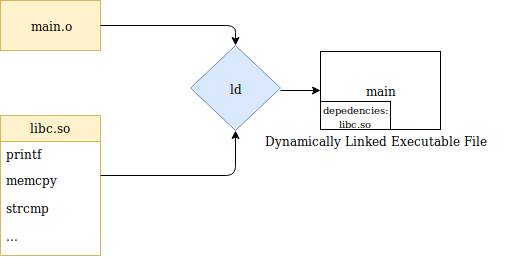

Dynamic linking, on the other hand, is a more complex process. Unlike in static linking, ld requires shared libraries to create a dynamically linked executable. The output file will contain the executable’s code and the names of the shared libraries required, embedded within the binary:

When the binary is executed, the dynamic linker will find the required dependencies to load and link them together. Thereby, deferring the linking stage from compile-time to run-time. We will detail how this process works shortly.

There are pros and cons to these two approaches:

- Static linking allows containing all dependencies in a single binary, making it more portable and simple to execute, at the expense of the file size.

- Dynamic linking allows the binary to be smaller, at the expense of having to ensure that the required dependencies exist in the target system that the binary will be executed in.

Dynamic linking

Pkg-config is a computer program that defines and supports a unified interface for querying installed libraries for the purpose of compiling software that depends on them. It allows programmers and installation scripts to work without explicit knowledge of detailed library path information.

It outputs various information about installed libraries. This information may include:

- Parameters for C or C++ compiler

- Parameters for linker

- Version of the package in question

!pkg-config --libs --cflags python3

-I/usr/include/python3.6m -I/usr/include/x86_64-linux-gnu/python3.6m -lpython3.6m

Now we’re able to compile a dynamic elf binary with the gcc compile and the following command :

!gcc test.c -o test_dyn $(pkg-config --libs --cflags python3)

!ls -ahl

-rw-r--r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 127K mai 9 17:31 test.c

-rwxr-xr-x 1 my_user_name my_user_name 46K mai 9 17:31 test_dyn

-rw-rw-r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 224 déc. 14 13:42 test.py

Let’s retrieve infos on the bin :

!file test_dyn

test_dyn: ELF 64-bit LSB shared object, x86-64, version 1 (SYSV), dynamically linked, interpreter /lib64/l, for GNU/Linux 3.2.0, BuildID[sha1]=60e013a1721bc3afb888c8a96cf7d69183335c6e, not stripped

The ldd command line (List Dynamic Dependencies) prints the shared libraries required by our program :

!ldd test_dyn

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fffbd948000)

libpython3.6m.so.1.0 => /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.so.1.0 (0x00007f788ab01000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f788a710000)

libexpat.so.1 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libexpat.so.1 (0x00007f788a4de000)

libz.so.1 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libz.so.1 (0x00007f788a2c1000)

libpthread.so.0 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpthread.so.0 (0x00007f788a0a2000)

libdl.so.2 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libdl.so.2 (0x00007f7889e9e000)

libutil.so.1 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libutil.so.1 (0x00007f7889c9b000)

libm.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm.so.6 (0x00007f78898fd000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f788b3b6000)

And check if it works on our OS (we’ll test it on other box later…):

!./test_dyn

name : Linux

name of machine on network : my_user_name-desktop

release : 5.3.0-51-generic

version : #44~18.04.2-Ubuntu SMP Thu Apr 23 14:27:18 UTC 2020

machine : x86_64

Static linking

How to statically link ELF binaries is explained in depth in this stackoverflow thread “Cython Compile a Standalone Static Executable”. Credits go to Mike Kinghan

libpython3.6m.a is the static version of the python3 library requested in our linkage commandline by pkg-config –libs –cflags python3.

To link a fully static executable (-static) when the linkage includes libpython3.6m.a, the linker must also find static (.a) versions of all the libraries that libpython3.5m.a depends upon1. The dynamic (.so) versions of all those dependencies are installed on your system.

That is why:

gcc test.c -o test $(pkg-config --libs --cflags python3)

succeeds, without -static. The static versions of those dependencies are not all installed on my system. Hence all the undefined reference linkage errors when you add -static.

!$ pkg-config --libs python-3.6

/bin/sh: 1: $: not found

and

!locate libpython3.6m.so

/opt/clion-2019.2.2/bin/gdb/linux/lib/libpython3.6m.so.1.0

/opt/clion-2019.2.2/bin/lldb/linux/lib/libpython3.6m.so.1.0

/usr/lib/python3.6/config-3.6m-x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.so

/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.so

/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.so.1

/usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.so.1.0

The dynamic dependencies of libpython3.6m.so are:

!ldd /usr/lib/python3.6/config-3.6m-x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.so

linux-vdso.so.1 (0x00007fffe6ec5000)

libexpat.so.1 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libexpat.so.1 (0x00007f72e9695000)

libz.so.1 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libz.so.1 (0x00007f72e9478000)

libpthread.so.0 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpthread.so.0 (0x00007f72e9259000)

libdl.so.2 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libdl.so.2 (0x00007f72e9055000)

libutil.so.1 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libutil.so.1 (0x00007f72e8e52000)

libm.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm.so.6 (0x00007f72e8ab4000)

libc.so.6 => /lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.so.6 (0x00007f72e86c3000)

/lib64/ld-linux-x86-64.so.2 (0x00007f72e9f72000)

We can disregard the first and last ones, which don’t look like regular libraries and indeed aren’t. So, I’d conclude that to satisfy the static dependencies of libpython3.6a, I need to install the static versions of:

libexpat

libz

libpthread

libdl

libutil

libm

libc

which will be provided by the dev packages of those libraries. Since my system is 64 bit Ubuntu, I’d then filter those dev packages by:

!dpkg --search libexpat.a libz.a libpthread.a libdl.a libutil.a libm.a libc.a | grep amd64

libexpat1-dev:amd64: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libexpat.a

zlib1g-dev:amd64: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libz.a

libc6-dev:amd64: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libpthread.a

libc6-dev:amd64: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libdl.a

libc6-dev:amd64: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libutil.a

libc6-dev:amd64: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libm.a

libc6-dev:amd64: /usr/lib/x86_64-linux-gnu/libc.a

and install them with:

sudo apt install libexpat1-dev zlib1g-dev libc6-dev

Then we can make the statically linking by adding those infos in the gcc compilation command :

!gcc -static test.c -o test_stat $(pkg-config --libs --cflags python3) -lm -lutil -ldl -lz -lexpat -lpthread -lc

!ls -ahl

/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/7/../../../x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.a(dynload_shlib.o): In function `_PyImport_FindSharedFuncptr':

(.text+0x7c): warning: Using 'dlopen' in statically linked applications requires at runtime the shared libraries from the glibc version used for linking

[...]

-rw-rw-r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 17K mai 9 14:12 linking1.png

-rw------- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 152K déc. 14 14:44 'python - Cython_ Compile a Standalone Static Executable - Stack Overflow.pdf'

-rw-rw-r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 9,8K mai 9 14:17 static_linking322.png

-rw------- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 99K déc. 15 15:50 'Static linking .so into my executable - Unix & Linux Stack Exchange.pdf'

-rw-r--r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 127K mai 9 17:31 test.c

-rwxr-xr-x 1 my_user_name my_user_name 46K mai 9 17:31 test_dyn

-rw-rw-r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 224 déc. 14 13:42 test.py

-rwxr-xr-x 1 my_user_name my_user_name 8,3M mai 9 17:43 test_stat

-rw-r--r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 21K mai 9 17:42 Untitled.ipynb

Let’s try if we can make the binary a little smaller by compressing it with a packer like UPX:

!cp test_stat test_stat_not_packed

!upx test_stat

Ultimate Packer for eXecutables

Copyright (C) 1996 - 2017

UPX 3.94 Markus Oberhumer, Laszlo Molnar & John Reiser May 12th 2017

File size Ratio Format Name

-------------------- ------ ----------- -----------

8621656 -> 3570952 41.42% linux/amd64 test_stat

Packed 1 file.

There is also an other option : strip the debug infos / symbols with -s option :

!gcc -static test.c -s -o test_stat_stripped $(pkg-config --libs --cflags python3) -lm -lutil -ldl -lz -lexpat -lpthread -lc

/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/7/../../../x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.a(dynload_shlib.o): In function `_PyImport_FindSharedFuncptr':

(.text+0x7c): warning: Using 'dlopen' in statically linked applications requires at runtime the shared libraries from the glibc version used for linking

/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/7/../../../x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.a(posixmodule.o): In function `posix_getgrouplist':

(.text.unlikely+0x3b53): warning: Using 'getgrouplist' in statically linked applications requires at runtime the shared libraries from the glibc version used for linking

/usr/lib/gcc/x86_64-linux-gnu/7/../../../x86_64-linux-gnu/libpython3.6m.a(posixmodule.o): In function `posix_initgroups':

[...]

!cp test_stat_stripped test_stat_stripped_not_packed

!upx test_stat_stripped

Ultimate Packer for eXecutables

Copyright (C) 1996 - 2017

UPX 3.94 Markus Oberhumer, Laszlo Molnar & John Reiser May 12th 2017

File size Ratio Format Name

-------------------- ------ ----------- -----------

6935784 -> 3065440 44.20% linux/amd64 test_stat_stripped

Packed 1 file.

We can confirm that those bins are indeed static ones :

!ldd test_stat_stripped_not_packed

not a dynamic executable

And the result is still the same when we launch the executable :

!./test_stat_stripped

name : Linux

name of machine on network : my_user_name-desktop

release : 5.3.0-51-generic

version : #44~18.04.2-Ubuntu SMP Thu Apr 23 14:27:18 UTC 2020

machine : x86_64

Conclusion

All the binaries produced work perfectly well on my OS, where they were compiled. They also work on a freshly installed xubuntu VM. But unfortunately this is not the case on a debian or alpine container :

sudo docker run -d -it debian

sudo docker cp test_dyn happy_pascal:/test_dyn

sudo docker cp test_stat happy_pascal:/test_stat

sudo docker exec -ti happy_pascal /bin/bash

root@8c71432c4346:/# ./test_dyn

./test_dyn: error while loading shared libraries: libpython3.6m.so.1.0: cannot open shared object file: No such file or directory

root@8c71432c4346:/# ./test_stat

Could not find platform independent libraries <prefix>

Could not find platform dependent libraries <exec_prefix>

Consider setting $PYTHONHOME to <prefix>[:<exec_prefix>]

Fatal Python error: Py_Initialize: Unable to get the locale encoding

ModuleNotFoundError: No module named 'encodings'

Current thread 0x00000000025c9900 (most recent call first):

Aborted (core dumped)

This is because, third party libraries needed for the libraries our bin has been linked against aren’t present or the same. This is a little bit frustrating because it means that our statically linked bins can only be run on the same OS with the same version and configuration…

There are also significant differences between the executables sizes. Obviously, the dynamic bin is smaller compared to static ones which include the python interpreter. As you can see there is also a gain with symbol stripping & packing with UPX :

!ls -ahl

-rw-r--r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 127K mai 9 17:31 test.c

-rwxr-xr-x 1 my_user_name my_user_name 46K mai 9 17:31 test_dyn

-rw-rw-r-- 1 my_user_name my_user_name 224 déc. 14 13:42 test.py

-rwxr-xr-x 1 my_user_name my_user_name 3,5M mai 9 17:43 test_stat

-rwxr-xr-x 1 my_user_name my_user_name 8,3M mai 9 17:44 test_stat_not_packed

-rwxr-xr-x 1 my_user_name my_user_name 3,0M mai 9 17:46 test_stat_stripped

-rwxr-xr-x 1 my_user_name my_user_name 6,7M mai 9 17:47 test_stat_stripped_not_packed